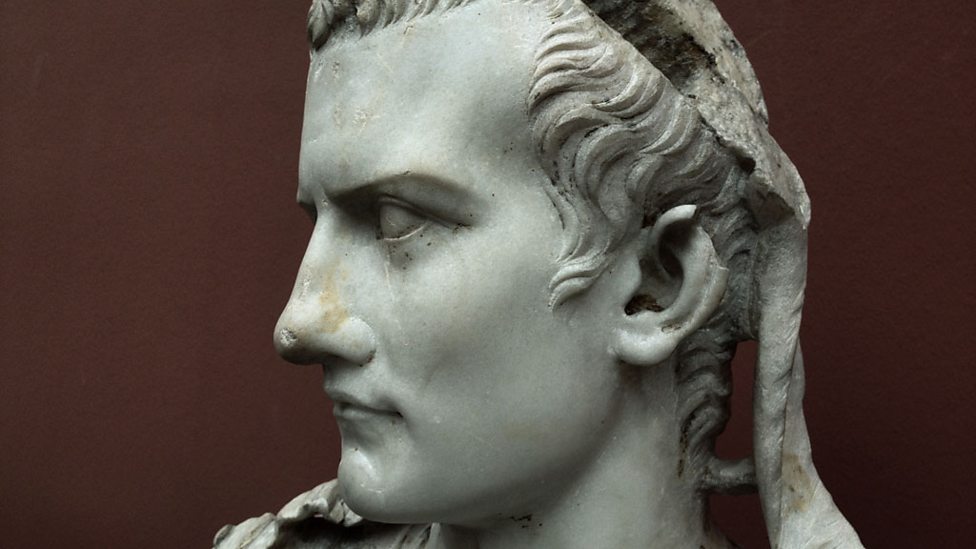

Caligula – Professor Mary Beard delves deep into the enigmatic legacy of Caligula, a name that sends ripples through history even today. Was he Rome’s most whimsical despot, or is there more than meets the eye?

Two millennia ago, Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, fondly remembered or infamously known as Caligula, stepped into the world’s theater. While his reign was brief, the tales of his exploits linger, painting a vivid portrait of a ruler like no other. Caligula’s reported escapades – from appointing his horse as a consul, to scandalous liaisons, and audacious architectural marvels – are tales that have stood the test of time. But how many of these narratives hold a candle to the truth?

Venture alongside Professor Beard as she embarks on a riveting quest, traversing the vast expanse of the Roman landscape – from the serene bays of Capri and Naples to the pulsating heart of imperial Rome. As we sail through these stories, often muddied by time and written long after Caligula’s abrupt end, glimmers of the ‘real’ Caligula emerge. One might catch a glimpse of him in the opulence of his private yachts anchored near Rome, or perhaps in the intricate designs he commissioned for his coins. Scraps of first-hand accounts, trial documents, and even records of his imperial staff breathe life into the enigma.

In this enthralling exploration, Mary deftly places Caligula within the tapestry of his era, unveiling a tale that pulsates with power plays, treachery, and familial ties that bind and break. As we peel back the layers of exaggeration and myth, a more nuanced figure emerges from the shadows. This journey isn’t just about unraveling the monster; it’s about understanding the man beneath the crown.

Join Professor Beard as she reconciles the man with the myth, painting a captivating narrative that bridges the past with the present. Understand why Caligula, despite his seemingly irredeemable reputation, remains an enigma that continues to fascinate, intrigue, and inspire.

Unmasking the Monster: Caligula with Mary Beard

Two thousand years ago, one of history’s most notorious individuals was born. Professor Mary Beard embarks on an investigative journey to explore the life and times of Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus – better known to us as Caligula.

Caligula has now become known as Rome’s most capricious tyrant, and the stories told about him are some of the most extraordinary of any Roman emperor. He was said to have made his horse a consul, proclaimed himself a living God, and indulged in scandalous orgies, and that’s before you mention building vast bridges across land and sea, prostituting senators’ wives, and killing half the Roman elite seemingly on a whim. All that in just four short years in power before a violent and speedy assassination in a back alley of his palace at just 29 years old.

Piecing together the evidence, Mary puts Caligula back into the context of his times to reveal an astonishing story of murder, intrigue,e, and dynastic family power. Above all, she explains why Caligula has ended up with such a seemingly unredeemable reputation. In the process, she reveals a more intriguing portrait of not just the monster, but the man.

The Making of a Tyrant

The first clear sight we have of Caligula in any historical record is a long way from Rome. From about the age of two, Caligula spent his childhood on the road, parcelled around from army camp to army camp with his mother Agrippina and his father Germanicus, one of Rome’s most charismatic military commanders.

By now, Rome had been under one-man rule for just 50 years. And a generation after the first Emperor Augustus, power was in the hands of one family – Caligula’s. His father Germanicus was the golden boy of the imperial family, tipped for the throne. His mother Agrippina was the granddaughter of the first Emperor Augustus himself. In the world of Ancient Rome, you didn’t get more blue-blooded than Caligula.

He was born Gaius Caesar Germanicus, a name he inherited from his father. These were the family fields of honor, the killing fields where Caligula’s ancestors cemented their reputations and political power. Today, the Roman Museum in Xanten has been built not far from one of the legionary camps where Caligula spent time as a boy. Inside, there is a collection of Roman military gear that reminds us Caligula’s childhood playground was not some cozy peacekeeping mission, but a vicious war zone.

Perhaps the museum’s most intriguing artifact is a perfectly preserved Roman caligae, a standard army-issue soldier’s sandal, made of tough leather with hobnails on the sole. The caligae is what Caligula is associated with. The story goes that when he was a boy living in military camps with his parents, his mother had him dressed up in the uniform of an ordinary Roman soldier, right down to the caligae. He was a kind of baby squaddie, the legionary mascot.

We tend to think of the name Caligula as a rather grand imperial name. It was the little boy’s nickname, meaning “little boots” or “bootykins”. When he grew up, Caligula hated it. It must have seemed as if he was being called Emperor Diddums. If you had asked him what his name was, he would have said his name was Emperor Gaius. The fact that we still call him Bootykins shows just how successful his enemies were in pouring scorn on him.

The Death That Changed Everything

In the 1960s, in the small hilltop town of Assisi in Umbria, a group of workers dug up an enormous bronze statue of Caligula’s father Germanicus that once stood on an army parade ground on the edge of town. It shows him in the classic pose of an imperial leader, arm outstretched, addressing his troops. Standing beneath him, one can’t help but sense the status and glamour of the man in whose shadow the little Caligula grew up.

One theory is that the statue was put up by Caligula himself after becoming Emperor, in memory of the event that radically changed the course of his life. For in 19 AD, when Caligula was just seven, Germanicus suddenly died on a mission to Syria, poisoned, he claimed from his deathbed, by the Roman Governor Piso, even perhaps under the orders of his uncle, the Emperor Tiberius.

When the news of Germanicus’s death reached Rome, there was an absolute explosion of grief. Life stopped, it’s said. Ordinary people wept in the street and wrote on the walls, “Give us back Germanicus.” The only people not grieving were the emperor and his mother. They weren’t seen in public and they didn’t authorise a full state funeral when Germanicus’s ashes came home.

Eventually, Piso was put on trial, but a few days in, he conveniently committed suicide and the trial was turned into a public inquiry. The bronze inscription tells us that the only person guilty was Piso, conveniently dead. But the most telling part is where it says copies are to be displayed across the Empire – mass communication, Roman style. A major attempt to get the official message across everywhere.

It’s hard not to think it was all too little, too late. The suspicions circling Germanicus’ death marked the start of an increasingly bitter feud between Caligula’s mother Agrippina and the Palace. Convinced Agrippina and her sons were plotting against him, Tiberius banished her to a remote island off Italy. And shortly afterward, he summoned Caligula, aged 19, to the island of Capri.

The Island of Corruption

Capri was the seat of Tiberius’ power away from Rome, where he ruled by proxy from imperial villas high in the cliffs. Tucked away in a museum on the island is a small trace of Caligula’s stay – a brick stamped with his name, Gaius Caesar. It’s the only evidence we have of his presence on Capri. Why Tiberius brought him and what he was doing remains a mystery.

Was he under surveillance? Was he there because Tiberius liked the kid? Or was he being groomed to be Emperor and to start building like one? Away from prying eyes, Roman writers later claimed, it was here that Tiberius schooled Caligula in the dark arts of tyranny and excess. The stories they told are fantastical – people chucked over cliffs, child prostitutes swimming between the emperor’s thighs. Whatever Tiberius got up to, we do know Caligula’s time in his charge was brutal.

While Caligula lived in luxury, his mother Agrippina was beaten up, starved,d and died. Both his brothers came to violent ends. One by one, he’d lost his father, mother, and brothers. He and his sisters were the only ones left. It’s a chilling reminder that in Rome, the closer you were to power, the harder it was to survive.

In the vaults of the British Museum is a marble skull that sums up the young Caligula’s life at court. It must have made a stunning centerpiece on the imperial dining table. Rich Romans loved the idea of eating, drink, and be merry because tomorrow you die. But in the flickering lamplight, any diner must have been aware their lives hung by a thread. The blurring of fake and real was one of the scariest factors of court culture. You never knew whether you’d be dead by morning.

A God Complex

When Caligula became Emperor at age 24, he made a song and dance of bringing his mother’s ashes to Rome, burying her in the family tomb built by his great-grandfather. The giant tombstone at the Capitoline Museums hammers home his right to rule through his lineage from Augustus. Caligula also minted coins stamped with his portrait to get his slogans across. They showed his royal bloodline and support from the army – no one could become emperor without military backing.

Without a military pedigree to earn respect, Caligula cast around for king-like leadership models. He presented himself as both Emperor and God. The boundary between emperors and gods was fragile and Caligula trampled through it. He insisted on being worshipped, transformed Rome’s Forum into his stage, and built a bridge to make chatting with Jupiter easier.

Archaeologist Henry Hurst has found evidence beneath the Forum that suggests these claims weren’t fantasy. Excavations revealed remains of a huge courtyard by the Temple of Castor and Pollux that could have been an imperial palace annex. The mystery platform by the Basilica Julia was the perfect height to be a pier supporting a raised walkway to the Capitoline Hill. Just a block of marble, but a clue that myths of Caligula’s megalomania contained truth.

Life in the Lap of Luxury

Caligula left his mark on Rome’s most iconic ancient monuments – the aqueducts, the Obelisk at St Peter’s, and the imperial Palatine residences. Traces of Caligulan splendor have also come from excavations of imperial pleasure gardens on Rome’s outskirts. Treasures include statues like the Sleeping Hermaphrodite, a saucy joke playing with gender. Hundreds of precious stones were found embedded in silver and gold – imagine them glittering in the palace walls.

Accounts say Caligula had a thing for pearls. He liked slippers decorated with them – a far cry from his childhood military boots. It’s a cute image, of the new emperor showing off his pearled slippers. But also an example of how the imperial family used ostentation to unsettle and disarm. This was the choreography of the threat lurking in palace life. You never knew what was real or fake.

One of the most iconic ancient Roman paintings is the Garden Room mural, designed for Caligula’s great-grandmother Livia. It’s an impossibly perfect garden scene that would have blurred the boundary between real and painted. The ambiguity was unsettling. What you think is harmless could turn out to be deadly. Like Caligula killing a practice opponent with a real dagger hidden in a wooden sword.

The Problem with Succession

Behind the palace’s culture of fear lay an issue the Roman Empire always struggled with – succession. With power now a family business, there was no fixed system for passing it on, a fatal flaw coloring Caligula’s story. When an emperor got old, rival factions jockeyed for power – the army, courtiers, palace slaves, and imperial women. It was very unstable.

This insecurity produced real violence and allegations of it. Nearly every emperor in the first century was rumored to be assassinated. Caligula himself was said to have smothered Tiberius to seize power. On becoming emperor, one of his first acts was to kill young Tiberius Gemellus, a rival heir. Conspiracies were inevitable in imperial life.

If Caligula seems paranoid, he has reason to watch his back. His brother-in-law was executed for plotting against him, and his wife and sister were exiled. The conspirators were inside the family, keen to replace him. The stories of his outrageous behavior that have defined Caligula’s legacy mostly start around now. And the most famous is about his horse Incitatus.

Myths of Madness

The idea Caligula made his horse a consul probably began as banter to needle the aristocracy. Ancient writers never actually say he did it. Underlying this myth is a power struggle with the Senate. They told outrageous stories of Caligula’s behavior to undermine his authority. Much of what seemed wrong with him related to sex.

He was said to have turned the palace into a brothel, becoming a byword for excess and perversion. We imagine orgies and incest with his sisters. If these tales have been embellished, they first appear years after Caligula’s death, mostly in the works of Suetonius. They tell us more about elite anxieties than about Caligula.

The stories portray the emperor humiliating the aristocracy with his power in disturbing ways, like stealing senators’ wives during dinner parties. The incest allegations also concerned the new influence of imperial women in politics. The stories show a young ruler without traditional credentials asserting his authority over an uneasy elite.

The Violent End

For all his watchfulness, Caligula didn’t evade his violent end. After just three years in power, he was assassinated at age 29 by officers of his guard, including Cassius Chaerea. This was no popular uprising, but a cold coup by the Praetorian Guard. They depended on an emperor to exist and simply installed another after Caligula’s death.

To justify their crime, the new regime damned Caligula as a tyrant. His building projects were appropriated, his image defaced, and his statues decapitated. The hybrid Claudius head in the Montemartini Museum underscores the awkward transition. With his real face lost, we must seek the real Caligula through other traces – on Capri, on the shores of Lake Nemi.

Conclusion

Sifting myth from reality across two millennia is impossible where little contemporary evidence survives. Maybe Caligula was an unhinged megalomaniac by the end. Maybe not. The tales are ambiguous. But he embodied tensions that came with autocracy – cruel power versus adoration, and the isolation of a despot from his subjects. His vivid afterlife in our imaginations reveals the deep unease tyrants produce and our conflicted responses to them.

In exploring Caligula’s enigmatic story, Mary Beard illuminates the exercise of absolute power and the treachery behind it. But she also prompts us to reconsider how we judge the characters of history. The abuses of tyrants may repel us. But deposing one tyrant for another teaches there are no simple solutions. Unmasking the human behind the myth, as Mary Beard has done, maybe the most enlightening thing of all.

FAQ – Unmasking the Monster: Caligula with Mary Beard

Why is Caligula considered a tyrant?

Caligula is seen as a tyrant because ancient sources describe him as cruel, unstable, and capricious. He was accused of incest, orgies, declaring himself a living god, and killing members of the elite. Modern historians debate how much is true.

Did Caligula make his horse a consul?

Ancient writers say Caligula planned to make his horse Incitatus a consul to insult the Roman elite but probably didn’t. The story reveals tensions between Caligula and the Senate.

How did Caligula change Rome’s architecture?

Caligula expanded Rome’s infrastructure, completing aqueducts and obelisks. He made improvements to imperial residences on the Palatine Hill and may have annexed temples in the Roman Forum.

Why was Caligula assassinated?

A conspiracy by officers of Caligula’s Praetorian Guard assassinated him after only 3 years ruling Rome. They sought to end his reign but primarily acted to install the next emperor rather than restore the Republic.

What happened to Caligula’s reputation after his death?

The new regime attacked Caligula’s memory as a tyrant. They appropriated his building projects, destroyed statues, and twisted facts to justify his murder. This assassination of his character influences his reputation today.