Picasso – The Beauty and the Beast episode 2 – Having ascended to an apex rarely seen in the artistic domain, Pablo Picasso, now a titan in the annals of art history, orchestrates an unparalleled solo exhibition in Paris, the city where culture and artistic innovation pulse through the streets. This show isn’t just an exhibition; it’s a declarative testament to his artistic prowess, drawing onlookers and critics into a world crafted by his genius.

However, even as his professional life reaches new heights, his personal life enters a phase of upheaval. Another romantic entanglement reaches its denouement, and amidst this emotional whirlwind, he commences a covert existence with a new companion, an enigmatic young woman barely 17 years of age. Their connection, both scandalous and passionate, adds yet another layer of complexity to Picasso’s already tumultuous life.

It’s against the stark backdrop of war’s devastation that Picasso finds potent inspiration, an ironic contrast where the darkness of the human condition offers fuel for artistic illumination. The turmoil of the era, the cries of despair, and the atmosphere of chaos become his muses, guiding his hand on the canvas. Out of this nexus of conflict and passion comes a surge of creativity that leads to some of his most significant, evocative works. Among them stands Guernica, not merely a painting but a profound social commentary—a visual manifesto against the atrocities of war, the suffering of civilians, and the tragedies often unnoticed by history’s victors.

This masterpiece, raw and unapologetic, captures the collective imagination, becoming a symbol of peace and a rallying cry for the preservation of life and beauty amidst destruction. This intense period, rife with personal and global crises, doesn’t just solidify Picasso’s place in the pantheon of legendary artists; it also highlights the intricate tapestry wherein his intimate emotional journeys and the broader strokes of world chaos blend indelibly, reflecting the depth of human experience in the strokes of his brush. Through this, Picasso doesn’t just live or create in his time; he immortalizes the very essence of it, presenting posterity with a mirror through which we might continually reassess our humanity.

Picasso – The Beauty and the Beast episode 2 – The Trials and Triumphs of Pablo Picasso: Amid Love and War, an Artist Immortalizes the Human Spirit

Surrealism’s Allure Intensifies as Picasso Reaches His Prime

Having ascended to an apex rarely seen in the artistic domain, Pablo Picasso, now a titan in the annals of art history, orchestrates an unparalleled solo exhibition in Paris, the city where culture and artistic innovation pulse through the streets. This show isn’t just an exhibition; it’s a declarative testament to his artistic prowess, drawing onlookers and critics into a world crafted by his genius.

However, even as his professional life reaches new heights, his personal life enters a phase of upheaval. Another romantic entanglement reaches its denouement, and amidst this emotional whirlwind, he commences a covert existence with a new companion, an enigmatic young woman barely 17 years of age. Their connection, both scandalous and passionate, adds yet another layer of complexity to Picasso’s already tumultuous life.

It’s against the stark backdrop of war’s devastation that Picasso finds potent inspiration, an ironic contrast where the darkness of the human condition offers fuel for artistic illumination. The turmoil of the era, the cries of despair, and the atmosphere of chaos become his muses, guiding his hand on the canvas. Out of this nexus of conflict and passion comes a surge of creativity that leads to some of his most significant, evocative works. Among them stands Guernica, not merely a painting but a profound social commentary—a visual manifesto against the atrocities of war, the suffering of civilians, and the tragedies often unnoticed by history’s victors.

This masterpiece, raw and unapologetic, captures the collective imagination, becoming a symbol of peace and a rallying cry for the preservation of life and beauty amidst destruction. This intense period, rife with personal and global crises, doesn’t just solidify Picasso’s place in the pantheon of legendary artists; it also highlights the intricate tapestry wherein his intimate emotional journeys and the broader strokes of world chaos blend indelibly, reflecting the depth of human experience in the strokes of his brush. Through this, Picasso doesn’t just live or create in his time; he immortalizes the very essence of it, presenting posterity with a mirror through which we might continually reassess our humanity.

In the early 1930s, Picasso reaches the midpoint of his life. Now 50 years old and firmly established as a seminal figure in modern art, his star appears to burn brighter than ever. However, lingering beneath this success simmers an undercurrent of unease. The specter of fading relevance haunts Picasso, like all great artists, as younger movements like Surrealism capture attention.

Desperate to reassert his supremacy in the French art world, he conceives of a plan—a solo retrospective exhibition on a scale far beyond any show devoted to a living painter. After securing a prime venue in Paris, Picasso hand-selects works from every period of his career, intentionally disrupting chronology to highlight his versatility. Cubist paintings mingle with Blue Period melancholy; glossy portraits waltz with sinister etchings. This thrilling cacophony of styles proclaims his mastery of reinvention.

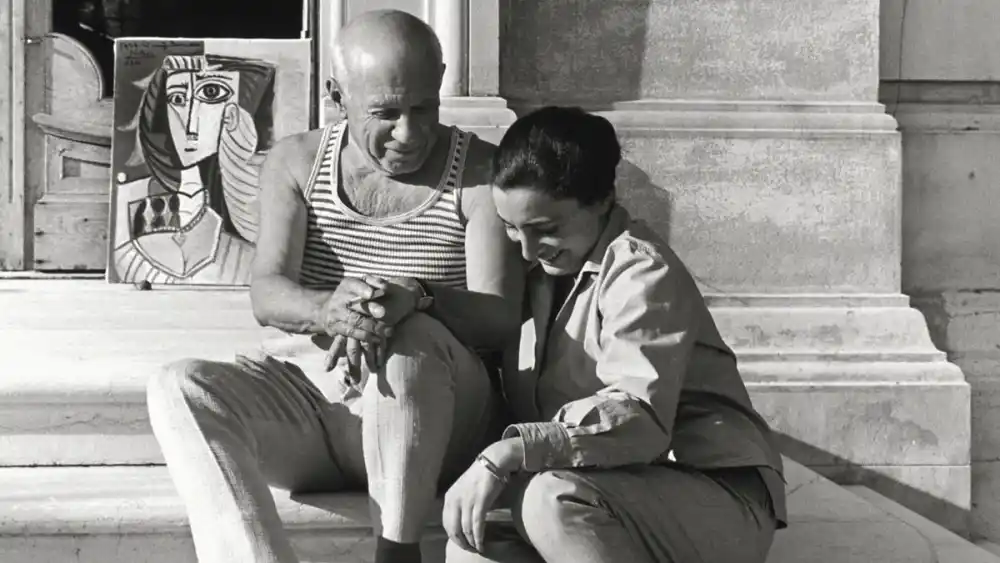

Though organized to flaunt his legacy, a corner of this exhibition hints at seismic upheavals underway in Picasso’s private affairs. His marriage to ballet dancer Olga Khokhlova frays as another woman captivates his gaze. Her likeness multiplies across canvases and etchings, a proliferation of golden hair and azure eyes. With this daring maneuver, Picasso brazenly introduces his new inamorata to society, heedless of consequences.

Picasso finds an unexpected wellspring of inspiration from this illicit romance. His young muse Marie-Thérèse Walter, just 17 when they meet, becomes his prized model and subject. Ensconced in his country estate, their trysts spark renewed creative vigor. Languid nudes and earthy sculptures exude sensuality. Stylistically, Picasso also evolves. Organic forms, soothing colors, and fluid lines convey blissful harmony. While legally still married with a son, Picasso pursues this relationship with single-minded zeal, appearing smitten like never before.

Through this cycle of upheaval—craving recognition, seeking stimulation, indulging passion—Picasso experiences an artistic renewal. Far from fading, his creative fires blaze hotter, ready to capture the defining spirit of these frenetic times.

Cubism’s Pioneer Becomes Coveted by the Avant-Garde

In the early 20th century, Picasso breaks ground by co-founding Cubism, the most radical artistic movement that century will witness. With fractured planes and rearranged perspectives, Cubism conquers the Parisian art scene, Picasso leading the charge. By distorting form and challenging convention, Picasso cements his status as an avant-garde provocateur.

However, what was once shocking becomes familiar. As Cubism’s novelty fades, Picasso finds himself yearning for fresh inspiration from creative kindred spirits. Luckily, Paris nurtures a thriving counterculture that’s home to exactly such a community—the Surrealists.

This merry band of artists, poets, and filmmakers make it their mission to channel dreams, probe the unconscious, and expose hidden realities. To tap their inner eccentric, they employ strange techniques meant to bypass rational thought. Exquisite corpse drawings, automatic writing, hypnotic trances—Surrealism embraces absurdity and irrationality as pathways to truth.

Picasso feels an instant kinship with these iconoclasts. Like him, they shun conformity and traditional mores. Also like Picasso, worldly success matters little next to their vocation. Displays of virtuosity take a backseat to authentic self-expression.

While wary of joining movements, Picasso adopts ideas from Surrealism that resonate deeply. Subjects like erotic desire, psychic automatism, and dream symbolism animate his work. Images morph and fuse; perspective and proportion abandon reality. In a way, Picasso comes full circle by returning to inner vistas which Cubism, for all its innovations, left unexplored.

Through cross-pollination with these kindred spirits, the 50-year-old Picasso reconnects to his creative essence. Far from fading into irrelevance, he stands ready to build upon his legacy. The fruits of this renewal will soon captivate the world.

Bohemian Companions Foster Artistic Awakening in Paris

When Picasso moves from Spain to Paris in 1904, he finds a vibrant community of fellow artists united by their devotion to innovation and disdain for convention. Unlike his homeland’s more rigid, academic attitudes to art, Paris nurtures daring experimentation. For ambitious mavericks like Picasso, it’s the perfect playground.

Key to Picasso’s rapid growth as an artist is this circle of avant-garde peers, who support and challenge one another. At the heart of this coterie are two close comrades—Carlos Casagemas, a Spanish expat like Picasso, and French artist Guillaume Apollinaire. Their camaraderie and spirited debates help the young Picasso expand his aesthetic horizons.

However, this fertile period ends abruptly with Casagemas’ tragic suicide in 1901, dealing an emotional blow to Picasso. Nevertheless, Picasso remains in Paris, his adopted home and site of his meteoric rise over the next decade. In fact, Casagemas’ death spurs Picasso to double down on his vocation, perhaps sensing the fragility of life.

With Apollinaire, Picasso finds an even more influential companion. Poet, critic, and agitator for modernism, Apollinaire serves as Picasso’s link to Parisian high society. He provides encouragement, critical feedback, and networking opportunities. When Picasso completes Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907, that seminal Cubist blueprint, Apollinaire grasps its significance. Their exchange of ideas helps Picasso synthesize radical influences like African masks into a new visual lexicon.

Through his immersion in this fertile environment, Picasso flourishes. Far from isolated, the young Spaniard joins a community equally obsessed with demolishing calcified traditions and forging new modes of expression. For Picasso, Paris nurtures a creative awakening, setting him on the path to legendary status. Had he stayed in Spain, this artistic giant might have never emerged.

Rivalry with Matisse Becomes a Wellspring of Inspiration

On his ascent to preeminence in 20th century art, Picasso finds a worthy rival in fellow French transplant, Henri Matisse. As trailblazers for modernism, their prolific outputs make them natural sparring partners engaged in a decades-long game of one-upmanship. This friendly rivalry proves mutually beneficial, encouraging both to outdo one another and vault to greater artistic heights.

Temperamentally, the two men diverge—Matisse deliberate and cerebral, Picasso impulsive and brimming with nervous energy. These contrasts filter into stylistic differences. Matisse pursues harmony through simplification of forms and soothing colors. Picasso gravitates toward emotional intensity conveyed through dramatic flourishes and exhilarating use of color.

Despite diverging styles, their shared quest to capture emotional truth pushes modern painting into new territory. Like scientists racing toward the same cure, their parallel breakthroughs enrich the era. Cubism, Fauvism, expressive use of color, fracturing of form—modern art owes much to their back-and-forth.

This rivalry hits a crescendo in the early 1930s. After Matisse’s triumphant retrospective exhibit in 1931, Picasso immediately starts planning his own solo show on a grander scale—like an athlete seeking to break a world record. This competitive impulse sparks renewed creative zeal in Picasso, inspiring some of his most important paintings.

Far from conflictual, their mutual admiration and ability to critique without malice made their rivalry fruitful. Both men benefitted enormously from having a contemporary genius against whom to test their mettle. For Picasso, this friendly competition generated energy when his inspiration flagged. More than admirers or dealers, only a peer of Matisse’s caliber could push him to excel.

Twisted Psyches Mesh as Picasso Meets His “Femme Fatale”

In the late 1930s, while romancing Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso becomes entangled with another magnetic woman possessing an altogether different temperament. He first encounters the brooding photographer Dora Maar in a chance meeting at Café aux Deux Magots, a famed gathering spot for Surrealists.

According to legend, Picasso was immediately transfixed by this mysterious beauty slashing her fingers with a penknife under the table. Unperturbed by the blood, Picasso introduces himself and secures her gloves as a keepsake. Thus begins their tumultuous nine-year relationship, spanning the Spanish Civil War and Second World War.

Maar appeals to Picasso not just physically, but as a conduit to Surrealist circles. Her connections to André Breton and Georges Bataille offer new stimulation for an intellect ever hungry for ideas. While less overtly artistic than painter Françoise Gilot, his next partner, Maar holds her own as a creative polymath, circulating in Paris’ cultural vanguard.

Psychologically too, each fulfills a need in the other. Just as Picasso enjoys dominating his partners, Maar inclines toward masochism. Picasso targets Maar’s insecurities with his habitual cruelty, accentuating her bouts of anguish. Yet Maar returns, hooked on Picasso’s genius and convinced only he can provide creative fulfillment.

Artistically, Maar’s influence manifests subtly, her cubist features morphing into Picasso’s weeping women. Through her network, Picasso also deepens his engagement with Surrealist themes of fantasy, sexuality, and nightmare. She becomes his documentarian of Guernica’s evolution.

Though ultimately confined to a supporting role, Maar occupies an important transitional period. After the serene Walter, Maar stimulates Picasso’s darker urges, priming him for further transgressions and unfettered exploration. Their mutual deleterious impact, while painful and destructive, spurs Picasso to new artistic heights.

Guernica’s Genius Stems from Picasso’s Rare Emotional Maturity

When Picasso begins painting Guernica in 1937, the horrors of Spain’s civil war offer endless artistic possibilities. Sacrilege, mutilation, suffering—the barbarism seems tailor-made for Picasso’s familiar arsenal of twisted imagery and grotesque deformations. However, something profound happens as Picasso confronts this subject. Rather than exploit the carnage stylistically, he strives to capture its meaning. His vision extends beyond formal or technical brilliance toward emotional truth.

This impulse manifests in Guernica’s restrained color scheme, dominated by stark blacks, whites, and grays. Though capable of visually sensationalizing the massacre, Picasso exercises uncharacteristic restraint. Similarly, clear symbolic forms communicate meaning directly, replacing his usual vertiginous experiments with perspective.

Guernica marks a zenith of Picasso’s ability to capture the zeitgeist. Through years grappling with weighty themes like war, morality, and cruelty, he understands events permeating daily headlines. Personal maturity enables this broader connection to humanity. The young rebel, eager to shock bourgeois tastes, evolves into an elder spokesperson for civilization’s conscience.

Picasso’s emotional wisdom permeates Guernica, particularly in its grief, resignation, and glimmers of hope. A century later, with history’s major convulsions behind us, its urgency feels undiminished. This universality stems from Picasso’s hard-won perspicacity regarding not just Spain’s anguish, but the shared human experience. Guernica resonates across continents and eras because, for once, Picasso paints not as an egotist fixated on his own psyche, but as a humanist able to see beyond it.

Picasso Normalizes Adultery, Flaunting Social Norms

Throughout his life, Picasso engages in countless liaisons, unconcerned with fealty or social opprobrium. First married in 1918 to ballerina Olga Khokhlova, Picasso soon chafes at domesticity’s constraints. By 1927, youthful model Marie-Thérèse Walter has replaced Khokhlova as his paramour and muse.

This affair offers copious artistic inspiration but causes domestic havoc. With mistresses unanimous that Picasso dislikes children, his wife bears the brunt of parenting alone. Laws also prohibited divorce, forcing Khokhlova to endure humiliation as Picasso flaunts his new lover publicly.

Beyond self-indulgence, Picasso pursues extramarital passions out of conviction that emotional truthfulness trumps vows. Since his art relies on exorcising inner demons, boredom and repression become anathema. When fascinated with Walter, suppressing these urges grew intolerable, even if socially transgressive.

Through his defiance of marital strictures, Picasso helped normalize the mistreatment of women socially ingrained in early 20th century Europe. For Picasso to follow his creative instincts required emotional libertarianism exempting him from vows that chained ordinary men. His extraordinary needs, in his view, superseded ordinary ethics.

This moral exceptionalism came at a price for the women subjected to his roving gaze. Like spectacles to be toyed with and discarded, Picasso left many lovers emotionally destitute once his fancy passed. But from the wreckage emerged artworks of enduring genius. Entangled in this complicated reckoning, Picasso’s legacy stands as a towering monument to artistic freedom and an indictment of its human toll.

Picasso’s Spanish Civil War Pacifist Stance Hardens in Exile

From 1936 to 1939, the Spanish Civil War pushes Picasso into an unaccustomed role—political activist. Though Spanish by birth, he resided abroad nearly all his life. However, with fascism’s specter looming, Picasso feels compelled to support his homeland’s embattled Republican government, including lobbying foreign governments for aid.

Initially confident the Republicans would prevail, Picasso believes morale-boosting propaganda is most useful. To that end, he paints Guernica, a passionate plea against nationalism’s horrors. Despite this, the Republicans lose, and a vengeful Franco vows to punish dissident artists like Picasso after victory.

With a return to his homeland impossible, Picasso grows disillusioned by his exile. No longer hopeful for reconciliation with Franco’s Spain, his sympathies shift further toward communism. While less overtly propagandistic than ally Rivera, Picasso’s leftist allegiances intensify. His 1955 Massacre in Korea elicits outrage from the American press, who label him a Stalinist hack.

Had Picasso returned to Spain, perhaps mellowed patriotism would have supplanted rigid ideology. But estrangement from his homeland leaves Picasso increasingly politicized. For the individualist Picasso, joining mass movements was an atypical decision motivated by lost Spanish identity and hostility toward fascism’s spread. Once cut off from Spain, revolutionary politics offer the aging artist a sense of belonging.

Conclusion

Picasso’s storied career reveals an artist of inexhaustible creativity, technical mastery, and cultural influence. Yet his output also lays bare his turbulent emotional life, with artistic evolution intrinsically linked to romantic entanglements.

In the 1930s, Picasso experiences renewed vigor, his lustful obsession with teenage muse Marie-Thérèse Walter inspiring joyous color and organic sensuality. This affair, conducted brazenly while married to wife Olga Khokhlova, highlights Picasso’s disregard for social norms when human passions beckon.

The 1940s bring crises personal and global, with Picasso remaining in Paris during Nazi occupation while also enduring inner demons. His wartime works exude a sinister air, augmented through collaborations with the Surrealists. Relationships with photographer Dora Maar and painter Françoise Gilot expose both Picasso’s cruelty toward women and the nourishing effect of their inspiration.

Politically, the loss of Spain, his homeland, to Francoist fascism pushes Picasso further toward rigid communism. No longer able to separate the personal and political, his art reflects Cold War ideology over individual expression. Yet masterpieces like Guernica remain iconic for their pacifist humanism, transcending specific historical moments.

At his core, Picasso inhabited many contradictions—communist and millionaire, pacifist and chauvinist, egoist and humanist. Accepting this totality allows us to separate the monumental creative legacy from the flawed mortal vessel. That his eventful life vibrates so intensely within his works remains Picasso’s gift to posterity. Through them, humanity’s complexities live on in vivid color.

FAQs

What inspired Picasso creatively during his midlife period in the 1930s?

Several factors led to a renewed creative period for Picasso in the 1930s, including rivalries with other artists like Matisse, influence from Surrealism, new romantic relationships like Marie-Thérèse Walter, political events like the Spanish Civil War, and a desire to assert his continued relevance against younger avant-garde movements.

How did Picasso’s relationships with women influence his art?

Picasso frequently used women in his life as artistic muses, painting many portraits inspired by his wives, mistresses, and lovers. Different women like Olga Khokhlova, Marie-Thérèse Walter, and Dora Maar inspired shifts in style and emotional tone during distinct periods of his career.

What major artworks did Picasso create in the 1930s?

Major 1930s works include Picasso’s solo exhibition in Paris, paintings inspired by Marie-Thérèse like Nude, Green Leaves and Bust, protest art linked to the Spanish Civil War like Guernica, and collaboration with the Surrealists in pieces like Minotaur series.

What was Picasso’s legacy as an artist?

Over his 70+ year career, Picasso produced an astounding oeuvre through nonstop innovation. He embodied the avant-garde ethos by repeatedly breaking with tradition in pursuit of new forms of expression. However, Picasso exhibited both the light and dark sides of creative genius through his artistic brilliance and callous treatment of others. Nonetheless, his influence on 20th century art remains unparalleled.